Where are Nigeria’s missing girls? On the hunt for Boko Haram

June 10, 2014

(CNN) — The license plates on our police escorts’ Land Cruisers read “Borno State, Home of Peace.” Many of those we meet during our stay in Maiduguri, northeast Nigeria, smile bitterly at the irony of that statement. The state’s capital is now better known as the birthplace of Boko Haram and peace here is always uncertain.

Down the dusty streets we drive, passing checkpoint after checkpoint manned not by soldiers but civilians, mostly armed with little more than machetes and swords. These vigilante groups, driven by a determination and motivation that the Nigerian security forces largely lack, have managed to establish some semblance of security in Maiduguri. Their pursuit of Boko Haram has become relentless — hardened as they are by losses to the terror group over the years — and they show no mercy, not even to family.

“I caught him with my hand and handed him over to the authority,” one of the sector’s leaders, Abba Ajikalli, tells us unapologetically. He is speaking about his 16-year-old nephew, who he says was with Boko Haram.

“He has been executed,” Ajikalli informs us, without a hint of remorse on his face. “He was like my son, I have no regret.”

What started as a home-grown movement for Sharia law in northern Nigeria is now a full-scale insurgency. Boko Haram attacks have terrorized this part of the country for years, but their kidnapping of nearly 300 schoolgirls in Chibok in April has brought them an unprecedented level of international infamy. Since then the insurgents, seemingly galvanized by the attention, have stepped up the frequency and brazenness of its attacks on villages in the region.

A presidential fact-finding mission is in Maiduguri at the same time as our trip. Each morning we receive word that they will travel to Chibok; each morning the residents and parents of the girls stolen from Chibok wait; and each afternoon everyone is disappointed by another postponement.

One woman, who is part of the mission and asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of the situation, told us that she would be quitting

“[The parents] need to know that the nation is with them, that people are with them,” she said emotionally. “But there are people that wouldn’t let us even call them. They keep saying it’s security and that’s why we can’t go, but some of us are willing to risk it.”

Abba Ajikalli, anti-Boko Haram vigilante

More than six weeks after the kidnapping, the Nigerian government and its forces have done little to ease the agony of the girls’ parents and those who have rallied behind the cause. Last week, officials banned all protests in support of the “Bring Back Our Girls” campaign, calling them “lawless,” before reversing tack in the face of a public outcry.

Traveling outside of Maiduguri is a risk, and our time on the ground is limited by security concerns. Just twenty minutes outside the city limits we find entire villages empty after recent attacks.

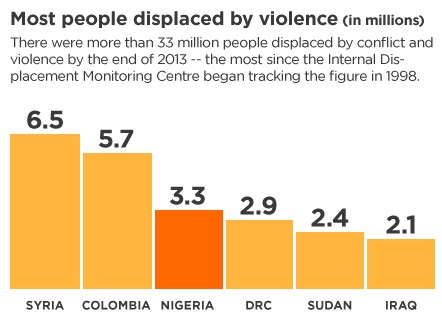

Maiduguri may be Boko Haram’s birthplace, but its terror is spreading. Refugees have been flowing into neighboring countries, where borders exist in name only, and each person has a harrowing tale of escape, a heartbreaking story of loss from which few will recover. The International Rescue Committee (IRC) estimates that as many as 1,000 refugees a week are crossing the border into Niger’s Diffa region. Four out of five are women and girls. The IRC estimates that if the violence continues in northern Nigeria, up to 100,000 refugees could be living in Diffa by the end of the year.

Orphaned by Boko Haram

All that 14-year-old Bintou and her little sister Ma’ou, 12, have of their former life in Nigeria are tattered photos of their parents.

Bintou curls up and buries her face, her shoulders shuddering with each silent sob. Ma’ou seems to have utterly internalized her pain, and speaks in a numb monotone.

They tell us they want to go back to Maiduguri, but for now they can’t. They are orphans — their mother died of natural causes before they can remember, and their father was killed in a Boko Haram attack about five months ago. We find them living with their aunt on a small plot in Diffa, Niger, uncertain about a future they are now forced to navigate alone.

“She [Bintou] can’t understand how this could have happened,” the IRC’s Mohammed Watakane, explains. “She is a victim going through a psychological trauma, she needs protection.”

Woman who fled Boko Haram attack

There are no refugee camps in Diffa, and Nigerians fleeing across the border have been absorbed into the local populations. The World Food Program is helping to ease the burden on host families by providing aid to the refugees, but it only has a quarter of the money it needs for its Niger programs, according to the country’s WFP director.

Read full on CNN: http://edition.cnn.com/2014/06/10/world/africa/boko-haram-hunt-arwa-damon/index.html