by Mayowa Tijani,

“I was with [Kenule] Saro-wiwa in 1992, 1993 when this manifold was shut, following some environmental threats,” Christian Lekova Kpandei, tells TheCable as he struggles to keep his motorcycle stable along a slippery marshy road baptised in oil and polluted rain drops.

Like many fishermen in Ogoniland, the lanky man in his late fifties had lost his fish farm and major source of livelihood to a heavy oil spill which turned his immediate home to a pool of black blood. Fish was no more, periwinkles were wrinkling in history, and crabs have become a thing of the past.

As the ecosystem degenerates into a shadow of itself, residents fear that they are inevitably the next set of casualties to fade off the face of this portion of earth they once — and always will — call home. They now have a date with death.

Agony does not begin to define what it means for a people to lose their loved ones, yield their homes to unwanted agents, watch their children drop out of school, and bury their livelihood — all to keep alive the hopes of the nation they call home. This is the story of Ogoniland.

Oil spills in Nigeria dates back to the 1970s, and according to the federal government, there were about 7,000 oil spills between 1970 and 2000. Since the turn of the new millennium, there have been incidents of spills recorded every year, up until 2014.

As at 2010, Royal Dutch Shell, admitted to have spilled nearly 14,000 tons (about 100,000 barrels of oil) in 2009, which was majorly across the oil-rich Ogoni. Since 2007, Shell has admitted 1,693 different spills, blaming them on sabotage of pipelines by youths in the Niger Delta.

According to Amnesty International, Shell and ENI, the Italian multinational oil giant, admitted to more than 550 oil spills in 2014 alone. Total oil spill in the region is estimated between nine and 13 million barrels.

In contrast, the entire Europe recorded only 10 spills between 1971 and 2011.

Kpandei, who also works with Amnesty International, says about 100 oil wells, estimated to account for about 120,000 barrels of oil per day, have been shut in the region, following the major Bodo spills in 2008 and 2009.

The spills was said to have ruined the livelihood of 69,000 residents, whose environment remain contaminated.

‘WE ARE WAITING FOR OUR DUE DATES WITH DEATH’

Monday Gbarage, the legal adviser to the Gbere Mene (King) of Gokana, and the council of chiefs and elders, says the Ogoni are dying in installment, and the living are only waiting for their due dates with death, in what he called the “Shell-shocked land”.

“For some years now, the area, as you can see, is regarded as the Gokana Shell-shocked land. This is Shell-shocked land because after a series of oil pollution in the land, Shell never deemed it necessary to remedy their wrong,” the lawyer said.

“The environment was not like this, but the stage it is now is more than a dilapidated building; the land is not useful for any economic activity. You can see the river, where our fishermen normally go for fishing. All these environment you can see behind was covered with thick mangrove — all is gone,” he said, pointing to the Bodo river, which had become a pitch dark shadow of itself.

“The oil pollution has impacted the adjoining lands. Farmers can no longer go to farm; there is low production. In some environment, there is no production at all, because you cannot cultivate.

“Talk about the air that is highly polluted? No drinking water, and bad air; the air we breathe in day and night is contaminated, the people are dying in installment. Even if you are living, you are only waiting for your due date.”

‘MY HUSBAND ALREADY HAD HIS DATE WITH DEATH’

A fish trader and mother of five, who simply identifies herself as Mary, says her husband was killed by the pollution of epic proportions, which ravaged the land after a series of oil spill.

“We had to eat contaminated dead fish,” Mary recounts as she fights her tears.

“He was complaining of stomach upset, and in no time began to purge, and this led to his death,” she says, adding that she now bears the burden of taking care of her five children, with no fish to sell. Her eldest daughter was married off to reduce the burden.

“I could no longer keep up with the fees, my children have been sent away from school,” she says with an apparent mix of pain and regret.

She and her family drink from the borehole water which the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) has declared “contaminated with high levels of hydrocarbons”.

‘NO PRIMARY HEALTHCARE CENTRE IN OGONI’

Patricia Kpor, another fish trader and mother of five, whose income is shrinking in similar proportion to the death of fishes in the Bodo river, in Gokana, said she made as much as N5,000 per day before the latest spill which affected the river.

“Now, on my lucky days, I make N3,000. Sometimes N2,000, N1,500 and on some days, I go home with nothing,” she says of her economic downturn.

Breathing the polluted air “has affected my lungs,” she tells TheCable. “I now have forceful breathing and some times unusual coughing.”

TheCable paid repeated visits to a number of state and privately-owned hospitals in the region, and found that the same manner of ailments described by the fish traders was predominant among the elderly in Ogoniland.

On the first visit to the Rivers State General Hospital in Bodo, TheCable saw a beautiful but empty hospital. One of the very few junior hospital staff around said the doctor was unavailable.

“Doctor no come today,” a junior staff told TheCable in pidgin English, asking that we return to the hospital at a later date, adding that patients already know what day the doctor will come.

Doctors are inadequate, and the few around in the state hospitals said the could not grant interviews as civil servants.

“I am from Ogoni, you can see things for yourself. Anything I tell you as an Ogoniman will be termed biased by politicians,” a doctor at the state hospital tells TheCable.

THE BREWING YOUTH BULGE AS A KEG OF GUN POWDER

Gahga Jandon is a fisherman and father of ten. He returns from Bonny River, about 30 kilometres away from his home in Gokana, with nothing to show for hours of fishing and paddling.

On arrival, he is welcomed by his son, James, who dropped out of secondary school at SS1 after his father’s business plunged. James is not disappointed, or rather, he is used to the “disappointment of no-catch”. He keeps hope in his eldest brother who is still on the waters, making a try.

With Jandon’s children back in the grim fishing business and out of school, and Mary’s children getting married off for survival, there is a dangerous youth bulge brewing in Ogoniland.

According to 2006 census, Ogoniland has a population of 831,726. Following the pattern of production in Nigeria, as highlighted by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the population of Ogoni is expected to have crossed a million as at 2017.

With a large chunk of fishermen and farmers losing their economic livelihood to pollution in Eleme, Gokana, Khana, and Tai, many children are dropping out of school and attempting to survive by all means.

LAI MOHAMMED: OGONI CLEAN-UP IS NOT NESCAFE

Exactly one year after the flag-off by Acting President Yemi Osinbajo was done on behalf of President Muhammadu Buhari, Lai Mohammed, minister of information, says the clean-up is not Nescafe coffee and cannot be done instantly.

“A lot has been done. There are preparations, there will be procedure for procurement, there will be logistics to be handled, and I think the last I heard, they have gotten to the level of procurement,” he said in an interview with Osasu Igbinedion.

“What government said is that as soon as we put in place the governing bodies, for the two organisations, then the donors, largely Shell, will now be able to bring the donation, and the federal government will bring its own. Yes, one drop of oil may not have been cleaned, but does not mean that people are not working.

“Somethings are not like Nescafe that you put in water and drink, there are procedures. The last time this was discussed at (the federal executive) council, the report was that they were near procurement.”

OGONI CHIEFS: GOVT SHOULDN’T COUNT ON OUR PATIENCE

Porobunu, chairman Gokana council of chiefs, says he can’t drink the water, says this is what I drink.

Micheal Tekuru Porobunu, chairman of the Gokana council of chiefs, who personally hosted the federal government and has the monument of the flag-off on his lawn, also tells TheCable that the government has not returned to the site of the flag off for over a year.

He says the exit of Amina Mohammed as the minister of environment was a “setback” for the Ogoni clean-up, but calls on the federal government not to count on the patience on the Ogoni people, who have been frustrated by the delay.

“I think in my capacity as the chairman of the Gokana council of chiefs, I should know if there is anything happening in Gokana. In fact, I should know if there is anything happening in Ogoni as a whole, that affects the clean-up,” he says.

“The paper work is yet to be done; for ten years we waited for government to get the paper work done. People have been suffering for 10 years and they are still doing paper work.”

He says the government may be doing its best but “their best is not good enough”.

Porobunu said the federal government and the international oil companies (IOCs) have been quiet since the flag-off was done within his compound a year ago.

“If you look at the flag-off, its been over a year now, at least show something. Nothing has been done. I live here, I breathe the air, I can’t drink the water; I buy water to drink, I buy water to cook, I am sitting on top of it. But I do believe that the government has good intentions,” he says.

“We are not protesting, we are just patiently waiting for the government to take action, but I think the government should not count on our patience, because sometimes patience runs out.”

BUT WHAT EXACTLY IS THIS CLEAN-UP?

A lot has been said about this clean-up of the oil spill, with little knowledge of what this clean-up entails. As the phrase suggests, clean-up is basically the extraction of pollutants from a place to return the site of the oil spill to its original or natural condition before the pollution occured.

TheCable speaks with Sulyman Abdulkareem, a professor of chemical engineering, and former vice chancellor of Al-Hikmah University, Ilorin, on what the clean-up entails and how Nigeria could go about returning Ogoni land to its original state.

According to the professor — who has done a lot of work on oil spill management in Nigeria and in the United States — there are seven major ways of cleaning oil spill, but the best is to use “olio sorbent materials”, which will physically remove the oil from water.

The Unilorin don, who invented a particular olio sorbent materials from “purewater sachet” in 2005, says his method was proposed by the Olusegun Obasanjo regime, and may be employed by the current administration.

“When there is a spill, you instantly respond so as to stop the spread. If it is on land, it is going to sink more, if it is on river, it is going to spread out more, which is going to become cumbersome and difficult to do,” he explains.

“There are many methods, but the one that is best is the one that separates oil from water, and that is achieved using boom or pillows or in this case, they can even use powder or the particle as made. The particle absorbs oil and leaves water intact, returning it to its original state, which is what you want.”

Other methods include bioremediation, floatation, sweeping up the oil, controlled burning of the oil, using dispersants to break down the oil particles, and gelling agents which solidifies spilled oil, making it easier to extract from water.

As for oil on land, UNEP and Abdulkareem recommend intensive soil washing, via a soil washing unit, which is expected to be set up as part of the clean-up.

UNEP further recommends the creation of three institutions for the clean up: Ogoniland Environmental Restoration Authority; Integrated Contaminated Soil Management Centre; and Centre of Excellence for Environmental Restoration in Ogoniland.

The UN environmental body also says the clean-up “will take 25 to 30 years to achieve and will require coordinated efforts by all tiers of government in Nigeria”.

CLEAN-UP TEAM: WE ARE ASSESSING THE SITUATION

Wale Edun, the chairman of the board of trustees for the clean-up, tells TheCable that machinery is in place for the necessary funding to come in for the entire exercise.

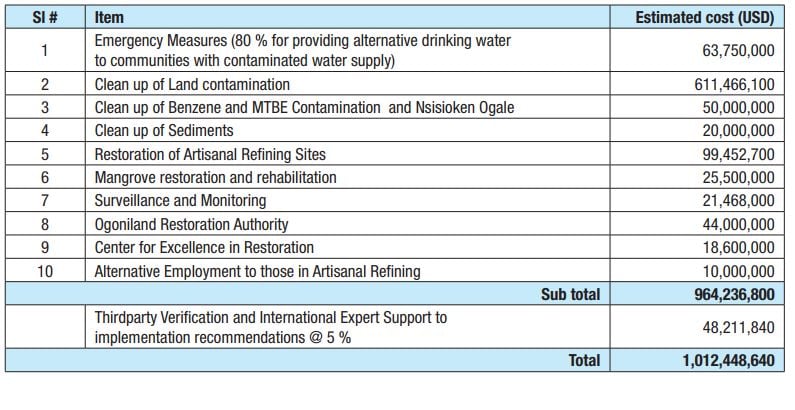

He acknowledges that the project cannot be called a success until the clean-up is done, stating that the structure is in place to raise a billion dollars over a period of five years for the project as recommended by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP).

“There is funding to start the process, funding is not what is holding us at the moment. The commitment is a billion over five years, and nobody has reneged on that till date. The structure to release the fund is in place,” Edun said.

Marvin Dekil, coordinator of the Hydrocarbon Pollution Restoration Programme (HYPREP), the body in charge of the clean-up, says his team is accessing the situation on ground — while training indigenes who will help with the clean-up.

“Right now, we are implementing the emergency measures and we are beginning to look at the water facilities in the area, assessing the cost of rehabilitating them,” he says.

“We are also in the process conducting demonstration projects, which allows companies with remediation technology to showcase at our site.”

Dekil, who was a technical assistant at UNEP, said his team, which was only called to action in April 2017, is currently working with the UN to train and sensitise residents for the clean up.

“We have also done some technical trainings for graduates of the environment; masters degree and above who are also from the Ogoni community, so they could participate in the remediation and develop skills and manpower in the area,” he says.

“We are developing women training scheme with UNITAR which is the training arm of the United Nations with the aim of providing them alternative livelihood. We would be doing more of the scoping of all the sites previously assessed by UNEP so as to get up-to-date status on the contamination.

“We are currently involved in sensitisation; going to the communities, explaning to them the deliverables of the project which are: remediation of the sites, and restoration of livelihood, that we have done in three local governments.”

He says “there has to be a start and we have started; that is the important message”.

BUHARI: HOPE DELAYED, HOPE DENIED?

When President Buhari promised a better life for the people of Ogoniland and flagged off a clean-up project, hope returned to the land; fishermen and farmers who had hitherto sought livelihood in other places were gearing up for a new life.

Stephen Porobunu, a fisher man, in Kegbara Dere, returned to his family pond after the flag off, to prepare the pond, which he inherited from his father for the new fishing season, which was to come after Buhari’s clean-up but his hopes have been delayed hitherto.

“If I were to speak to President Buhari, I will tell him that we are all human beings, and he is supposed to do something so we can all survive. All these mangrove is gone; we are left with nothing but sufferings,” he laments.

“Since I rehabilitated my pond, I caught some fish and brought in here, but they all died. Now there is nothing inside. Fishes cannot live here because of the oil,” he said, pointing in the direction of his empty pond and oily nets.

Like Porobunu, boat makers were optimistic and returned to the business of making new boats in anticipation of new fishing activities. But their hopes have also been delayed, making boats with no one to buy. They say for them, Buhari needs to prove that hope delayed is not hope denied.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Published materials are not the views of the MacArthur Foundation.